Why Stringless Guqin House?

Years ago a beautiful lady poet invited Luo Fu, one of the most famous poets of our time and Nobel Literature Prize nominee, and his wife for lunch at a restaurant in Harrison Hot Springs, a popular hot springs resort town within driving distance from Vancouver. The poetic charm of the lakeside and surrounding mountains there made a wonderful backdrop for lunch. The honor of providing transportation to this lovely couple additionally earned me a seat at the same lunch table.

On the way there, we had a very pleasant conversation. At some point, the topic drifted towards my residence. The couple mentioned that they liked my place – quaint yet elegant, and tastefully decorated with a generous collection of old philosophy books, calligraphy and famous guqins. True enough, I grew up with the Four Arts of Chinese scholars (guqin, chess, literature and painting).

And while on that topic, I took the opportunity and asked if he would pick a name for my residence.

After pondering for a moment, his eyes lit up and he said briskly, “Stringless House”. Intrigued, I asked him how he came up with the name, and if it referred to the stringless guqin referenced in Buddhist literature.

To which Luo Fu replied “No”. Instead, he said, the name was inspired by a well known poet named Tao Yuanming.

Sidebar

Tao Yuanming (陶淵明 365? – 427) was a major poet during the Eastern Jin Dynasty, a period which ushered in a united China at the conclusion of the warring chaos of the Three Kingdoms Period. Like many of the scholars before him, he was disillusioned with public life. He withdrew from civil service and returned to a subsistent life style, in which he enjoyed the simple pleasures of reading, writing poems, drinking wine, playing guqin and hanging out with friends, despite running into occasional financial difficulties. In self portrait “Mr. Five Willows Chronicle” (《五柳先生傳 》) , he described his own predicaments:

On how he got his name:

“Nobody knows where he comes from or his name. Next to his house there happened to have five willows, so hence how he was to be known.” ( “先生不知何許人也,亦不详其姓字,宅邊有五柳樹,因以為號焉。”)

On his personality and love for wine:

“Quiet and rarely talks; disinterested in fame and material gains; fond of reading and never frets about not catching all the meanings; and often forgets about food whenever getting caught up in his reading.” (“閒靜少言,不慕榮利。好讀書,不求甚解;每有會意,便欣而忘食。”)

“He loves wine, but cannot always afford it. Knowing his circumstances, his friends and relatives would invite him over and serve him wine.” (“性嗜酒,家貧不能常得。親舊知其如此,或置酒而招之。”)

On his shabby abode and state of financial welfare:

“Bare walls all around; do not quite shelter from the elements.” (“環堵蕭然,不蔽風日。”)

“Clothing frayed and patched; food vessels often empty, but totally relaxed.” (“短褐穿結,箪瓢屢空,晏如也。”)

“Totally relaxed” with his less-than-humble living conditions was further evidenced by one of his immortal poetic verses: “Picking chrysanthemums along the east fence, the southern hills casually come into view” (“採菊東籬下,悠然見南山。”), in which he expressed his enjoyment of the simple pleasures of life.

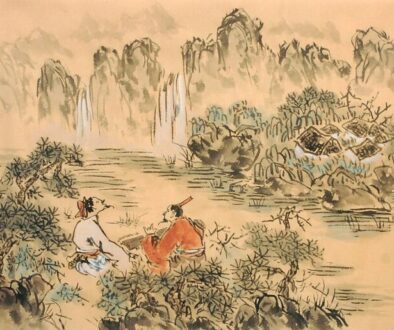

His passion for guqin was no less than his love for wine and reading. His guqin, however, was just a wooden board with some or all of the cords missing. Cords were made of silk back then and they would eventually snap after prolonged use, and he likely could not afford to replace the broken ones. Hence, ‘primitive’ would be a very charitable characterization of his guqin.

Nonetheless, the lack of a decent instrument did not deter him from playing. On the contrary, he treated his guqin like a treasure and was rarely seen without it by his side. Drinking was always accompanied with playing music, with him often passing out while engaged in his two passions.

Drinking and playing guqin by himself in his house was one thing, doing so with good friends was quite something else. Whenever he gathered with them, he would bring his stringless ‘guqin’ along. While his friends played theirs, he would pretend to be striking and stroking the cords as if the missing cords were there.

His friend would ask what he was doing, to which he replied, “Once you appreciate the joy of guqin, who needs the sounds that come out of it?” (“但識琴中趣,何勞弦上音?”)

(Image source: m.linban.com)

Luo Fu continued, “Tao Yuenming played a stringless guqin. Through playing, he sought a state of mind which transcended the sounds coming out of the instrument. He refused to stoop so low for his pay cheques and left civil service. His poems and essays are natural and without excesses, fully reflecting his joy of returning back to nature. His lofty ideals and morality shines through the primitive hut and worn-out clothing that define his physical world and shower over pine trees, chrysanthemums and rain clouds.”

“He caused me to think about your life style. Aren’t you also devoted to the improvement of your guqin music? You immerse yourself among the plants and flowers every day, and yet still manage to calm your state of mind in order to study Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. Moreover, with your vegetarian diet, you are almost half way up there above this earthly world. As such, to borrow “Stringless House” from Tao Yuanming is most appropriate.”

Being mentioned along with this immortal poet in the same breath, I was flattered yet embarrassed by such praise undeservedly bestowed. While he undoubtedly overestimated my abilities, shouldn’t his imparting inspire me to follow the footsteps of these luminaries before me?

It was because of his encouragement that I further devoted myself to the art of guqin, and, in June 2016, opened my guqin studio, duly named Stringless Guqin House, in memory of that epiphanic exchange.

Through the Zen of stringless guqin, soothing taste of tea and lingering of incense, Stringless Guqin House will strive to create an oasis for the purity and tranquility of mind.